<small>* estimation based on tests on an internal development team, building production applications.</small>

-## Sponsors

+## Sponsors { #sponsors }

<!-- sponsors -->

<a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/fastapi-people/#sponsors" class="external-link" target="_blank">Other sponsors</a>

-## Opinions

+## Opinions { #opinions }

"_[...] I'm using **FastAPI** a ton these days. [...] I'm actually planning to use it for all of my team's **ML services at Microsoft**. Some of them are getting integrated into the core **Windows** product and some **Office** products._"

---

-## **Typer**, the FastAPI of CLIs

+## **Typer**, the FastAPI of CLIs { #typer-the-fastapi-of-clis }

<a href="https://typer.tiangolo.com" target="_blank"><img src="https://typer.tiangolo.com/img/logo-margin/logo-margin-vector.svg" style="width: 20%;"></a>

**Typer** is FastAPI's little sibling. And it's intended to be the **FastAPI of CLIs**. ⌨️ 🚀

-## Requirements

+## Requirements { #requirements }

FastAPI stands on the shoulders of giants:

* <a href="https://www.starlette.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Starlette</a> for the web parts.

* <a href="https://docs.pydantic.dev/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Pydantic</a> for the data parts.

-## Installation

+## Installation { #installation }

Create and activate a <a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/virtual-environments/" class="external-link" target="_blank">virtual environment</a> and then install FastAPI:

**Note**: Make sure you put `"fastapi[standard]"` in quotes to ensure it works in all terminals.

-## Example

+## Example { #example }

-### Create it

+### Create it { #create-it }

Create a file `main.py` with:

</details>

-### Run it

+### Run it { #run-it }

Run the server with:

</details>

-### Check it

+### Check it { #check-it }

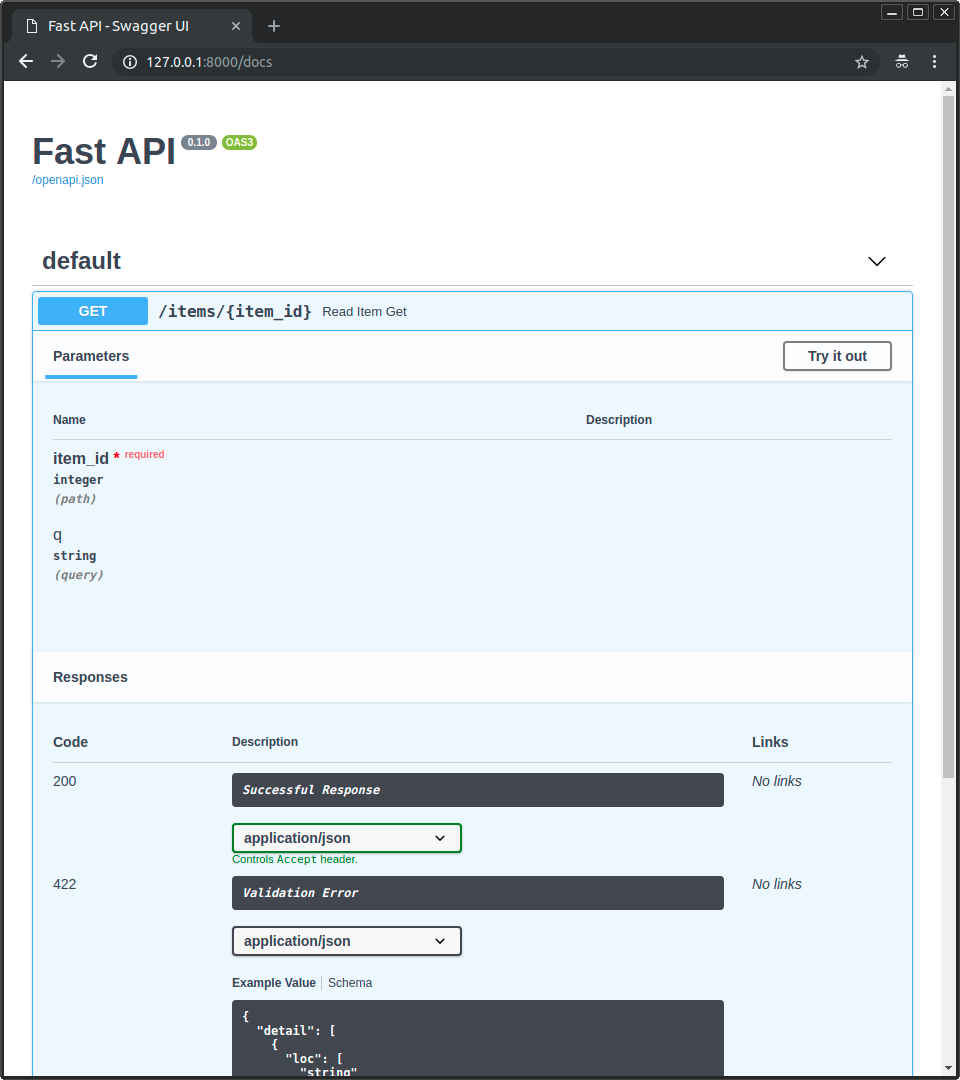

Open your browser at <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/items/5?q=somequery" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/items/5?q=somequery</a>.

* The _path_ `/items/{item_id}` has a _path parameter_ `item_id` that should be an `int`.

* The _path_ `/items/{item_id}` has an optional `str` _query parameter_ `q`.

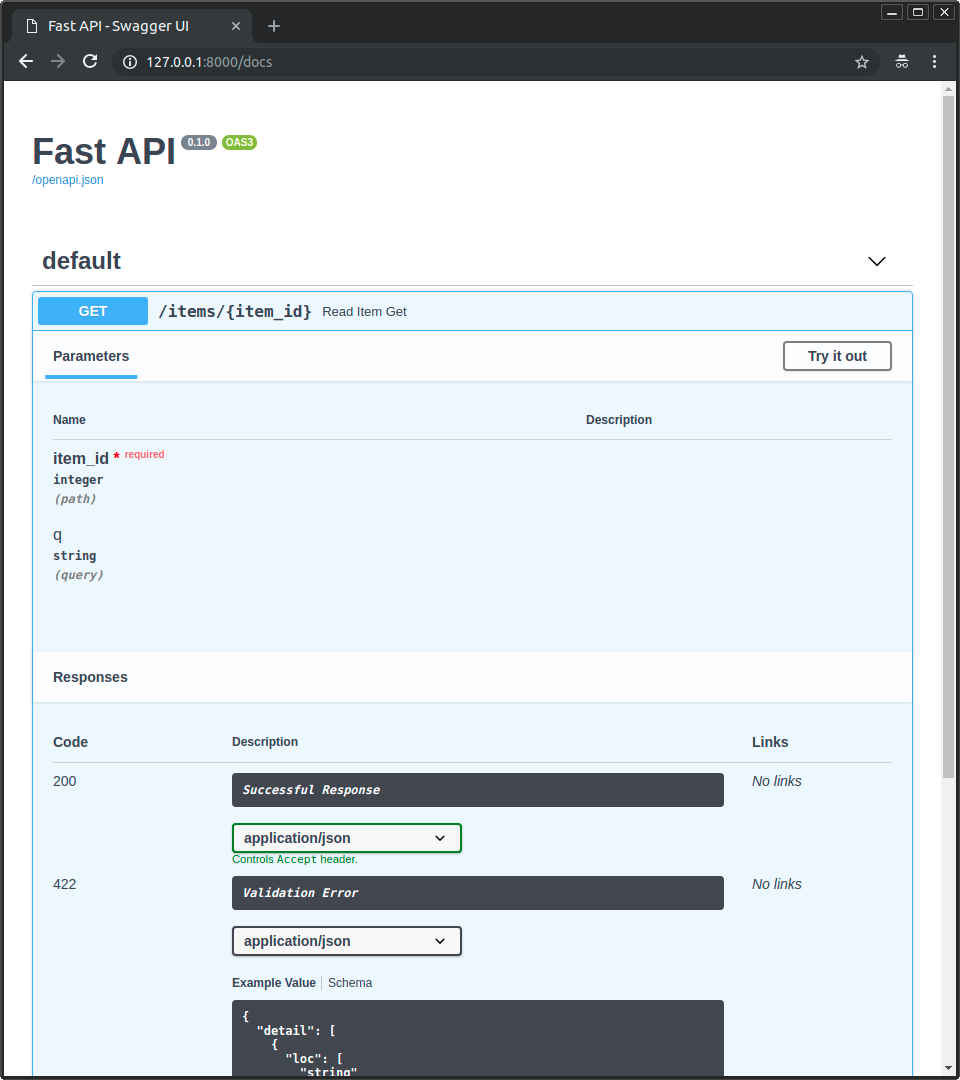

-### Interactive API docs

+### Interactive API docs { #interactive-api-docs }

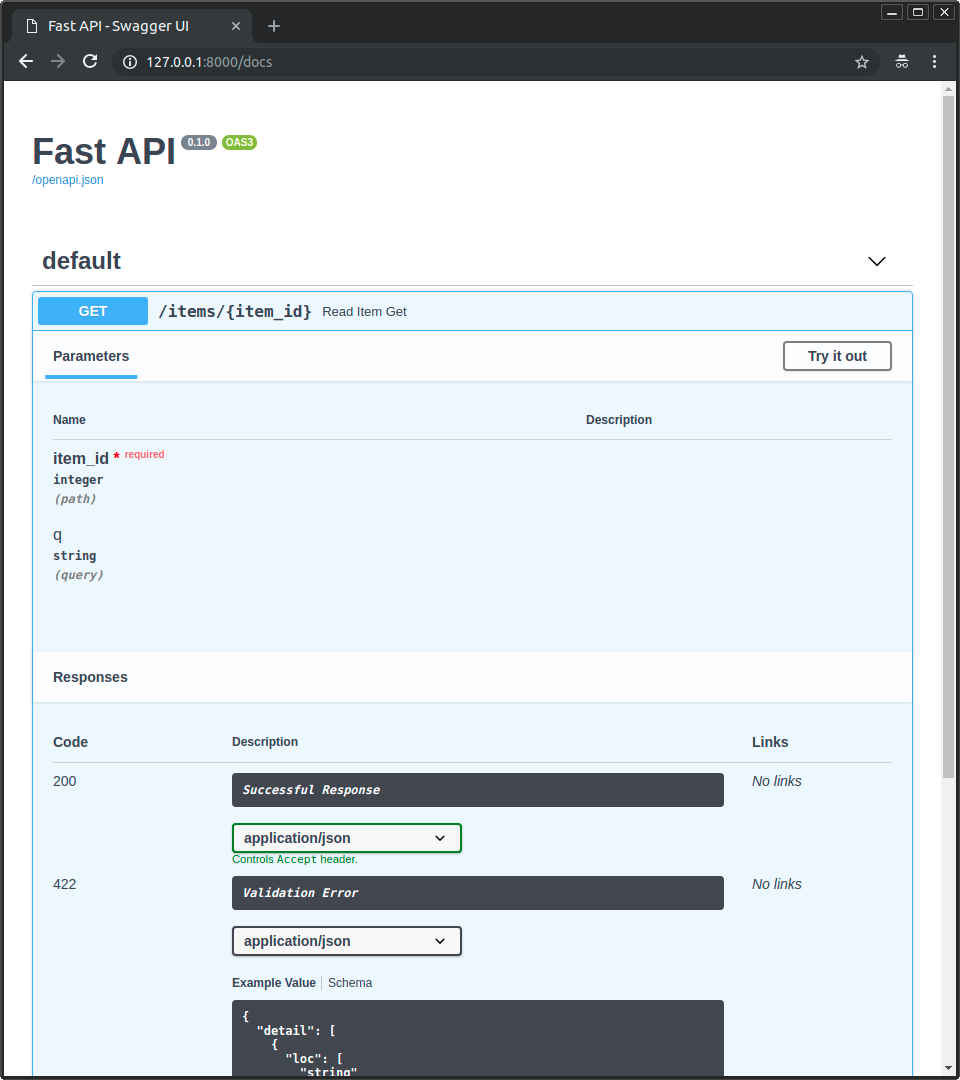

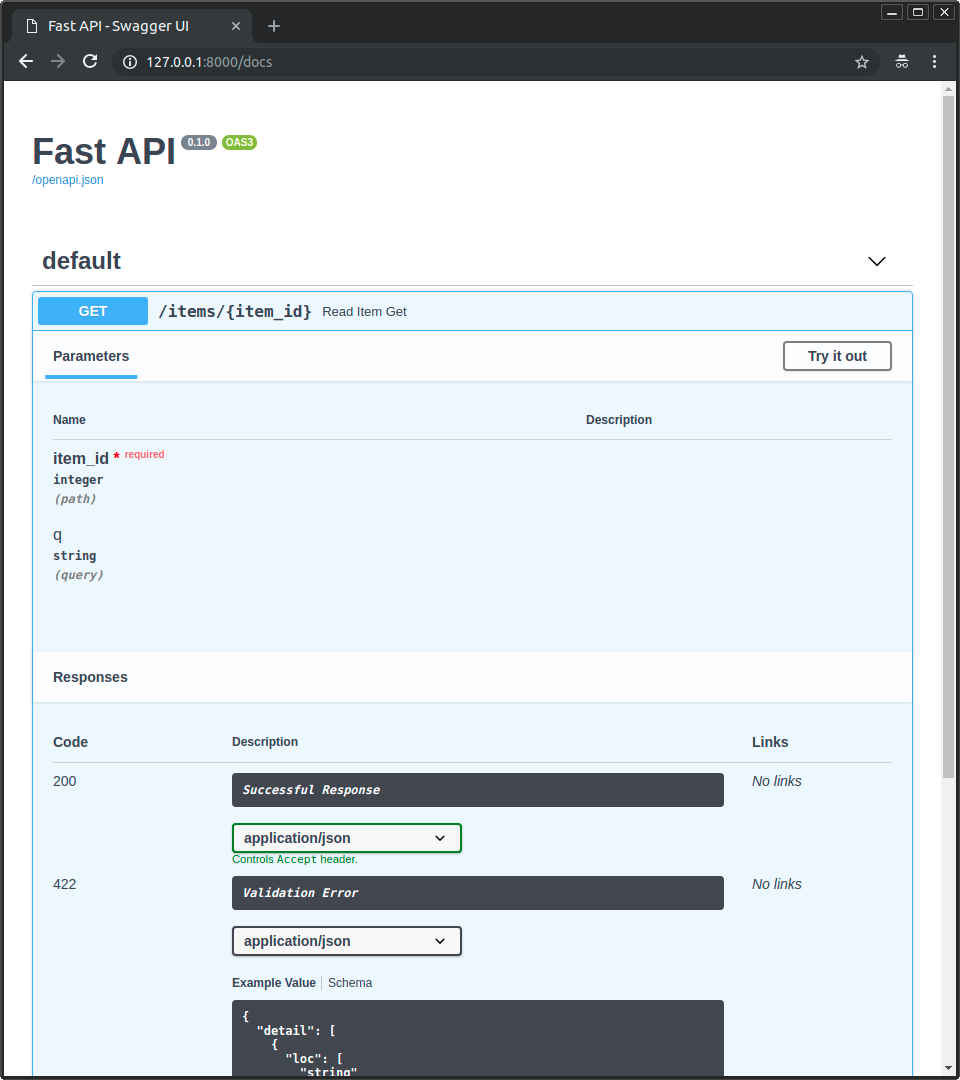

Now go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

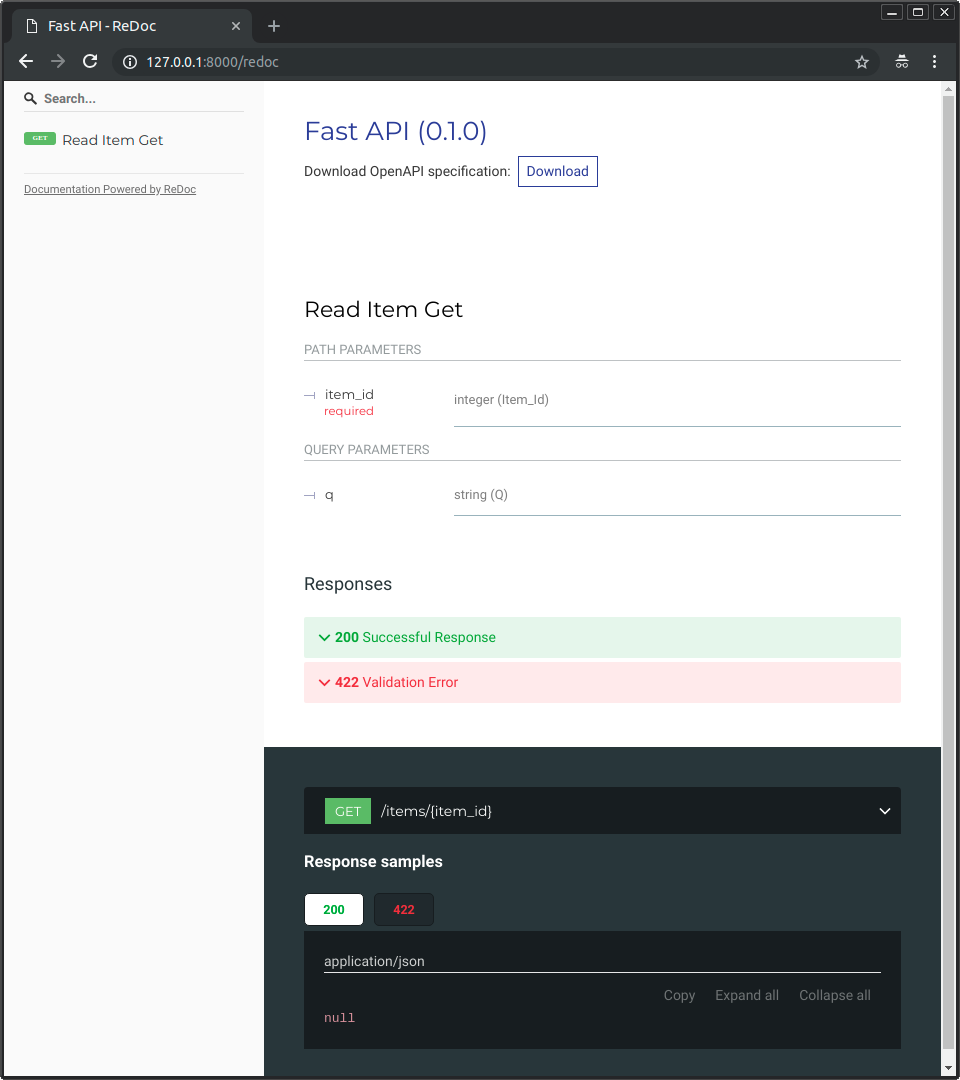

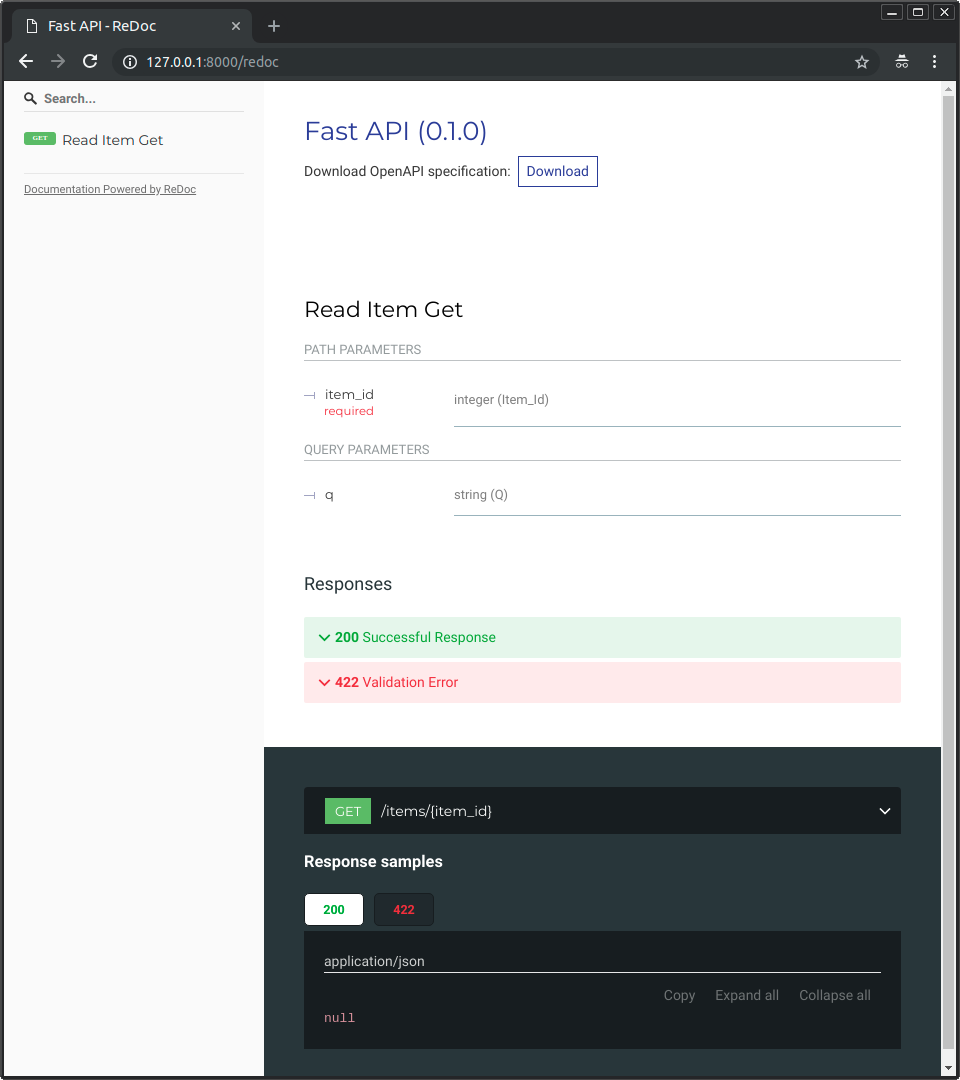

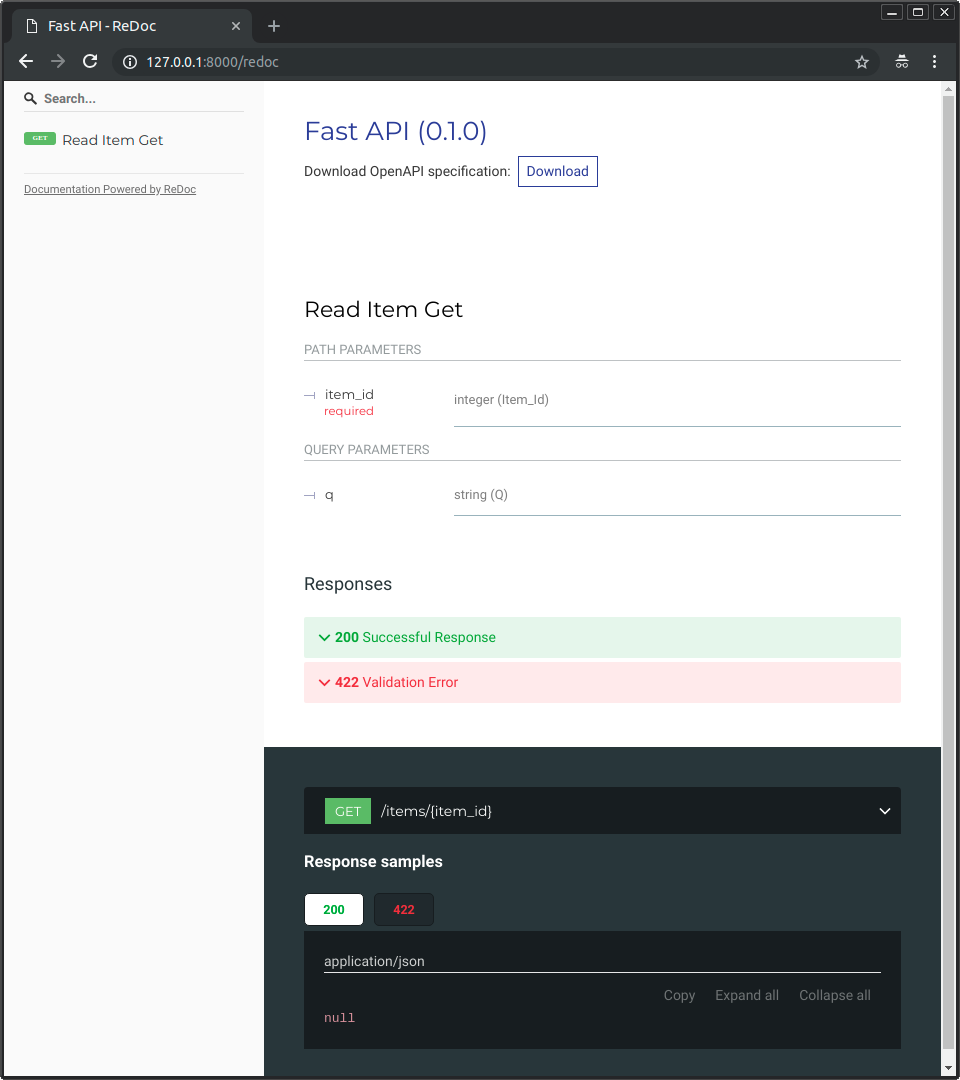

-### Alternative API docs

+### Alternative API docs { #alternative-api-docs }

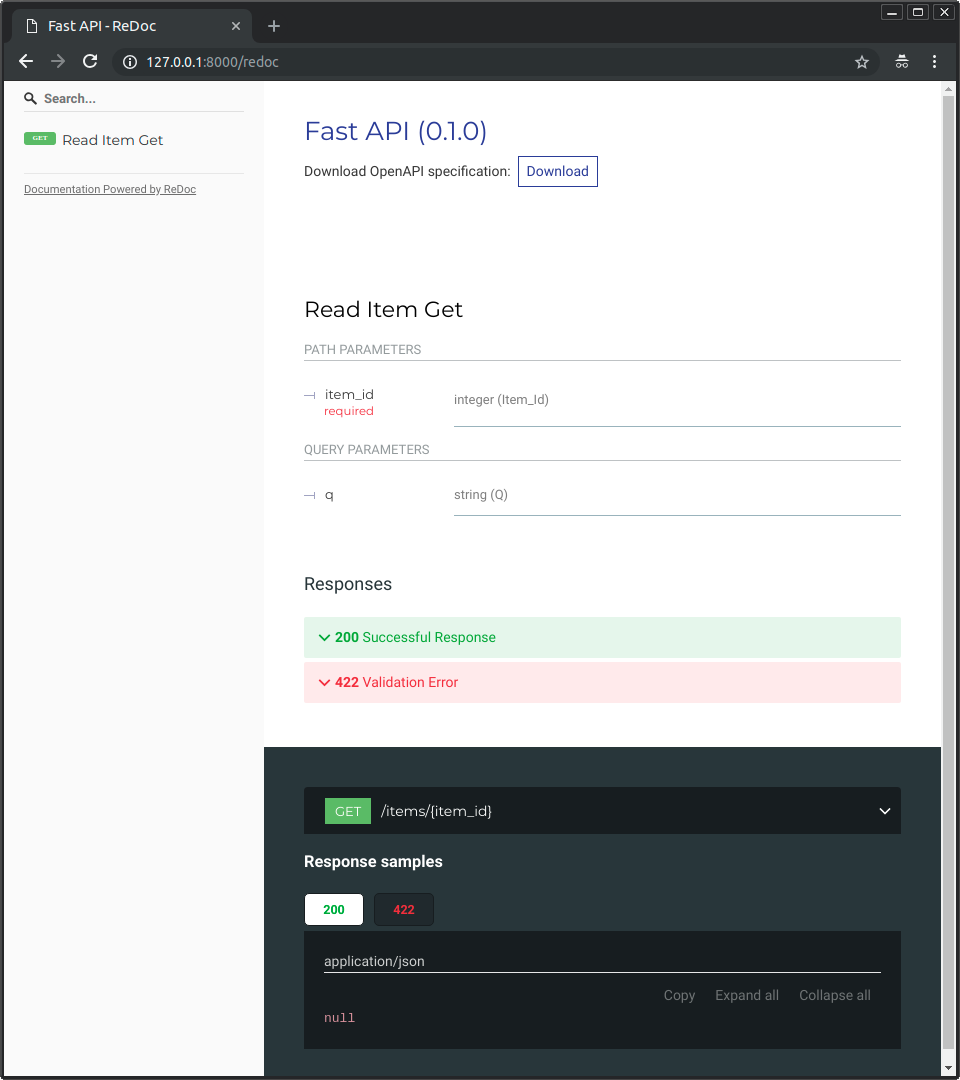

And now, go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc</a>.

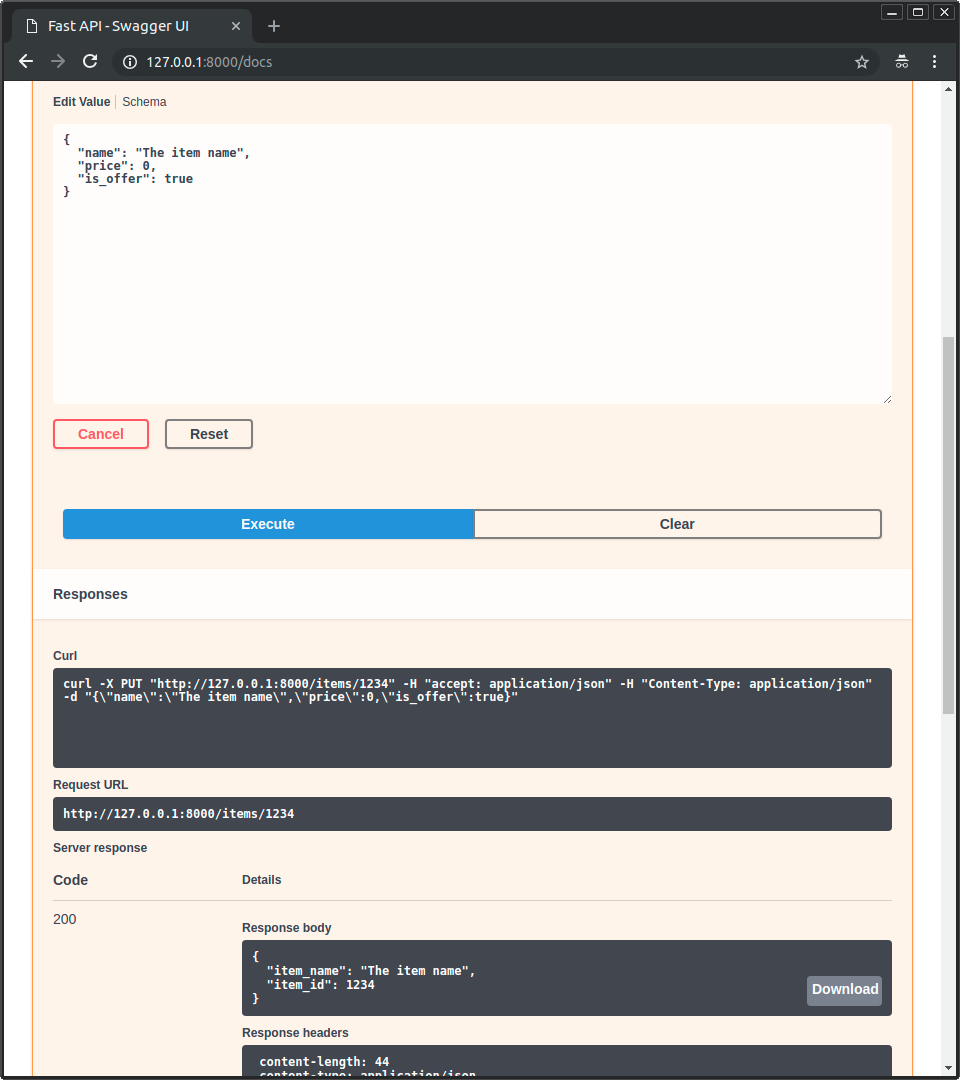

-## Example upgrade

+## Example upgrade { #example-upgrade }

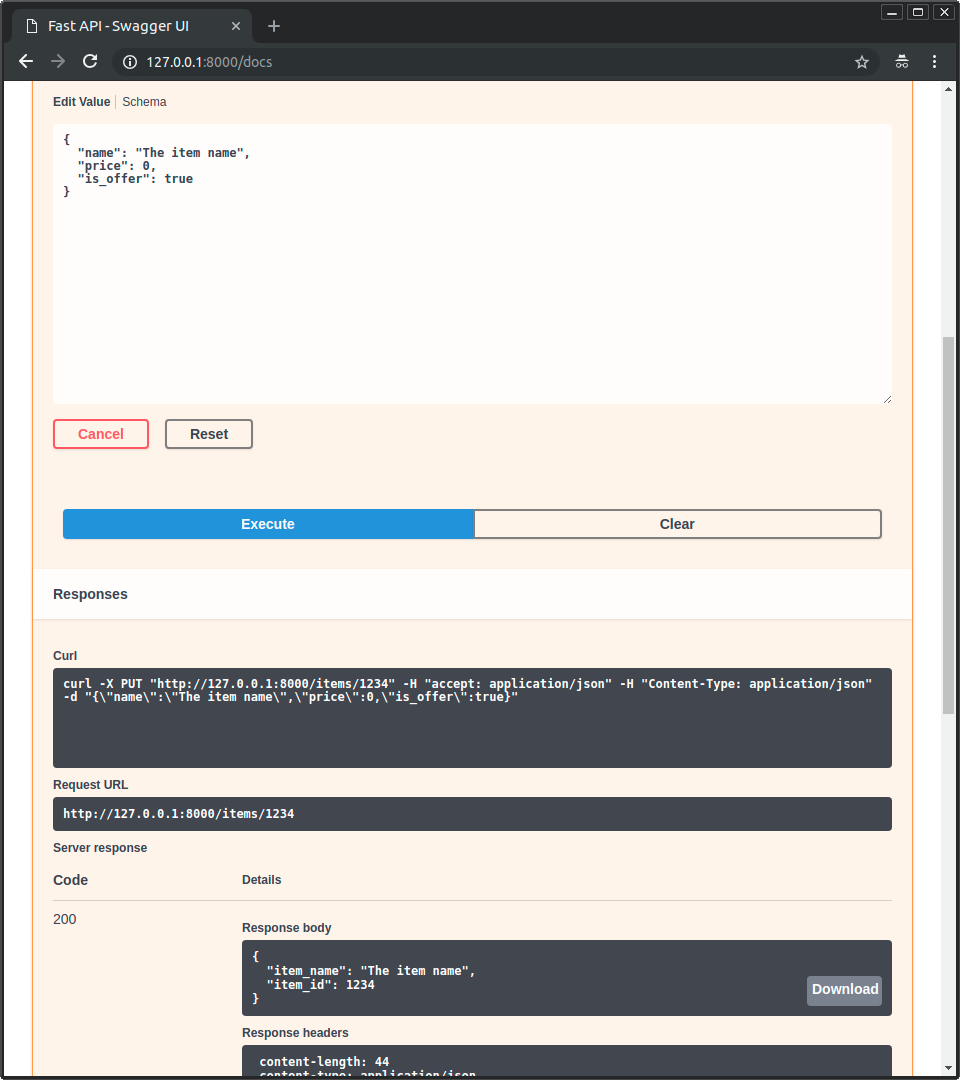

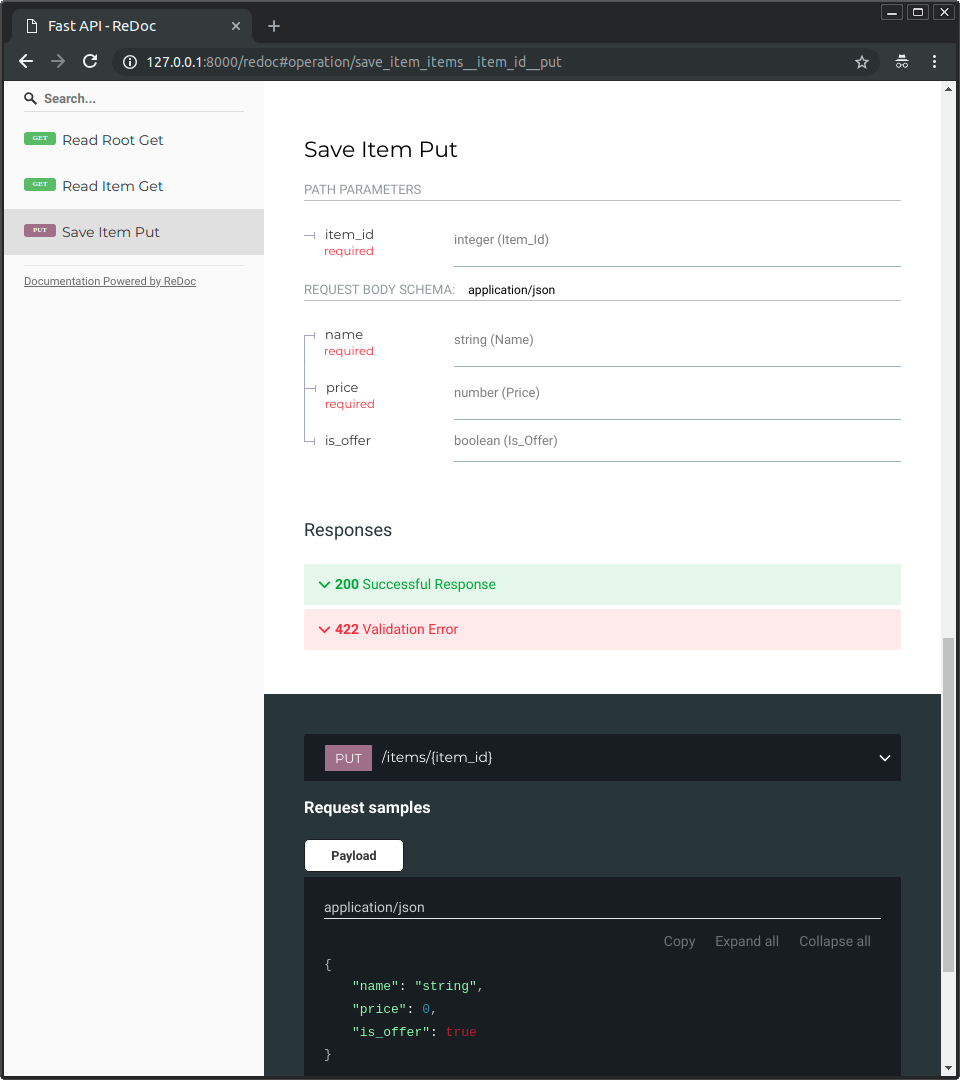

Now modify the file `main.py` to receive a body from a `PUT` request.

The `fastapi dev` server should reload automatically.

-### Interactive API docs upgrade

+### Interactive API docs upgrade { #interactive-api-docs-upgrade }

Now go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

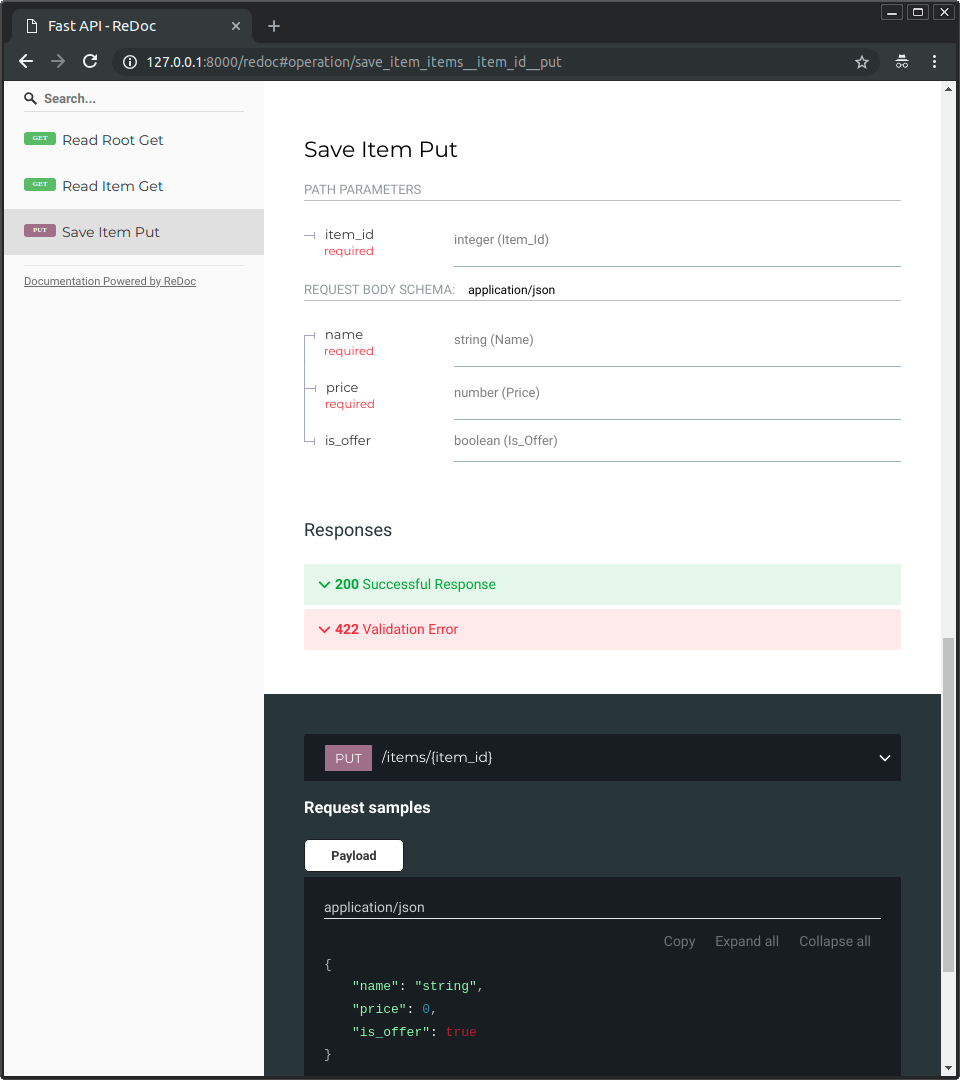

-### Alternative API docs upgrade

+### Alternative API docs upgrade { #alternative-api-docs-upgrade }

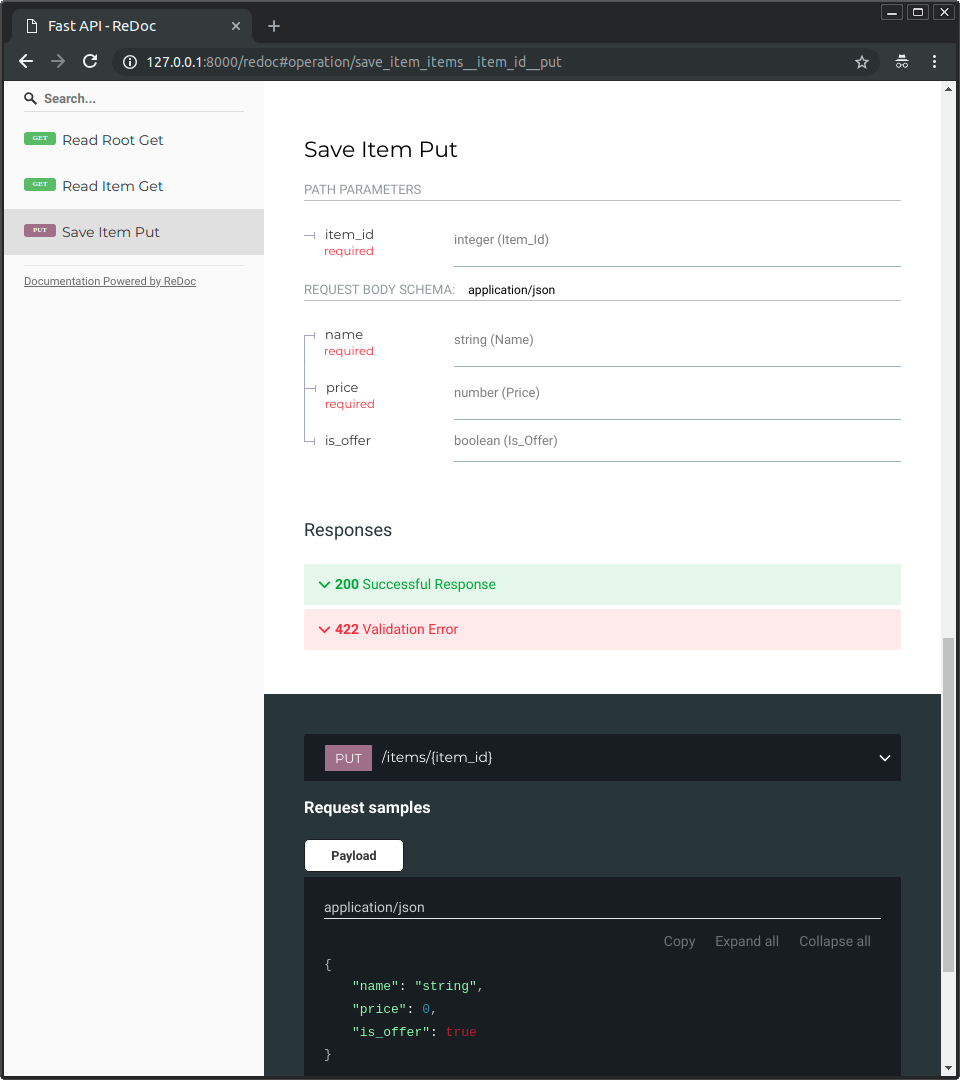

And now, go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/redoc</a>.

-### Recap

+### Recap { #recap }

In summary, you declare **once** the types of parameters, body, etc. as function parameters.

* **Cookie Sessions**

* ...and more.

-## Performance

+## Performance { #performance }

Independent TechEmpower benchmarks show **FastAPI** applications running under Uvicorn as <a href="https://www.techempower.com/benchmarks/#section=test&runid=7464e520-0dc2-473d-bd34-dbdfd7e85911&hw=ph&test=query&l=zijzen-7" class="external-link" target="_blank">one of the fastest Python frameworks available</a>, only below Starlette and Uvicorn themselves (used internally by FastAPI). (*)

To understand more about it, see the section <a href="https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/benchmarks/" class="internal-link" target="_blank">Benchmarks</a>.

-## Dependencies

+## Dependencies { #dependencies }

FastAPI depends on Pydantic and Starlette.

-### `standard` Dependencies

+### `standard` Dependencies { #standard-dependencies }

When you install FastAPI with `pip install "fastapi[standard]"` it comes with the `standard` group of optional dependencies:

* `fastapi-cli[standard]` - to provide the `fastapi` command.

* This includes `fastapi-cloud-cli`, which allows you to deploy your FastAPI application to <a href="https://fastapicloud.com" class="external-link" target="_blank">FastAPI Cloud</a>.

-### Without `standard` Dependencies

+### Without `standard` Dependencies { #without-standard-dependencies }

If you don't want to include the `standard` optional dependencies, you can install with `pip install fastapi` instead of `pip install "fastapi[standard]"`.

-### Without `fastapi-cloud-cli`

+### Without `fastapi-cloud-cli` { #without-fastapi-cloud-cli }

If you want to install FastAPI with the standard dependencies but without the `fastapi-cloud-cli`, you can install with `pip install "fastapi[standard-no-fastapi-cloud-cli]"`.

-### Additional Optional Dependencies

+### Additional Optional Dependencies { #additional-optional-dependencies }

There are some additional dependencies you might want to install.

* <a href="https://github.com/ijl/orjson" target="_blank"><code>orjson</code></a> - Required if you want to use `ORJSONResponse`.

* <a href="https://github.com/esnme/ultrajson" target="_blank"><code>ujson</code></a> - Required if you want to use `UJSONResponse`.

-## License

+## License { #license }

This project is licensed under the terms of the MIT license.

-# About

+# About { #about }

About FastAPI, its design, inspiration and more. 🤓

-# Additional Responses in OpenAPI

+# Additional Responses in OpenAPI { #additional-responses-in-openapi }

/// warning

But for those additional responses you have to make sure you return a `Response` like `JSONResponse` directly, with your status code and content.

-## Additional Response with `model`

+## Additional Response with `model` { #additional-response-with-model }

You can pass to your *path operation decorators* a parameter `responses`.

}

```

-## Additional media types for the main response

+## Additional media types for the main response { #additional-media-types-for-the-main-response }

You can use this same `responses` parameter to add different media types for the same main response.

///

-## Combining information

+## Combining information { #combining-information }

You can also combine response information from multiple places, including the `response_model`, `status_code`, and `responses` parameters.

<img src="/img/tutorial/additional-responses/image01.png">

-## Combine predefined responses and custom ones

+## Combine predefined responses and custom ones { #combine-predefined-responses-and-custom-ones }

You might want to have some predefined responses that apply to many *path operations*, but you want to combine them with custom responses needed by each *path operation*.

{* ../../docs_src/additional_responses/tutorial004.py hl[13:17,26] *}

-## More information about OpenAPI responses

+## More information about OpenAPI responses { #more-information-about-openapi-responses }

To see what exactly you can include in the responses, you can check these sections in the OpenAPI specification:

-# Additional Status Codes

+# Additional Status Codes { #additional-status-codes }

By default, **FastAPI** will return the responses using a `JSONResponse`, putting the content you return from your *path operation* inside of that `JSONResponse`.

It will use the default status code or the one you set in your *path operation*.

-## Additional status codes

+## Additional status codes { #additional-status-codes_1 }

If you want to return additional status codes apart from the main one, you can do that by returning a `Response` directly, like a `JSONResponse`, and set the additional status code directly.

///

-## OpenAPI and API docs

+## OpenAPI and API docs { #openapi-and-api-docs }

If you return additional status codes and responses directly, they won't be included in the OpenAPI schema (the API docs), because FastAPI doesn't have a way to know beforehand what you are going to return.

-# Advanced Dependencies

+# Advanced Dependencies { #advanced-dependencies }

-## Parameterized dependencies

+## Parameterized dependencies { #parameterized-dependencies }

All the dependencies we have seen are a fixed function or class.

But we want to be able to parameterize that fixed content.

-## A "callable" instance

+## A "callable" instance { #a-callable-instance }

In Python there's a way to make an instance of a class a "callable".

In this case, this `__call__` is what **FastAPI** will use to check for additional parameters and sub-dependencies, and this is what will be called to pass a value to the parameter in your *path operation function* later.

-## Parameterize the instance

+## Parameterize the instance { #parameterize-the-instance }

And now, we can use `__init__` to declare the parameters of the instance that we can use to "parameterize" the dependency:

In this case, **FastAPI** won't ever touch or care about `__init__`, we will use it directly in our code.

-## Create an instance

+## Create an instance { #create-an-instance }

We could create an instance of this class with:

And that way we are able to "parameterize" our dependency, that now has `"bar"` inside of it, as the attribute `checker.fixed_content`.

-## Use the instance as a dependency

+## Use the instance as a dependency { #use-the-instance-as-a-dependency }

Then, we could use this `checker` in a `Depends(checker)`, instead of `Depends(FixedContentQueryChecker)`, because the dependency is the instance, `checker`, not the class itself.

-# Async Tests

+# Async Tests { #async-tests }

You have already seen how to test your **FastAPI** applications using the provided `TestClient`. Up to now, you have only seen how to write synchronous tests, without using `async` functions.

Let's look at how we can make that work.

-## pytest.mark.anyio

+## pytest.mark.anyio { #pytest-mark-anyio }

If we want to call asynchronous functions in our tests, our test functions have to be asynchronous. AnyIO provides a neat plugin for this, that allows us to specify that some test functions are to be called asynchronously.

-## HTTPX

+## HTTPX { #httpx }

Even if your **FastAPI** application uses normal `def` functions instead of `async def`, it is still an `async` application underneath.

The `TestClient` is based on <a href="https://www.python-httpx.org" class="external-link" target="_blank">HTTPX</a>, and luckily, we can use it directly to test the API.

-## Example

+## Example { #example }

For a simple example, let's consider a file structure similar to the one described in [Bigger Applications](../tutorial/bigger-applications.md){.internal-link target=_blank} and [Testing](../tutorial/testing.md){.internal-link target=_blank}:

{* ../../docs_src/async_tests/test_main.py *}

-## Run it

+## Run it { #run-it }

You can run your tests as usual via:

</div>

-## In Detail

+## In Detail { #in-detail }

The marker `@pytest.mark.anyio` tells pytest that this test function should be called asynchronously:

///

-## Other Asynchronous Function Calls

+## Other Asynchronous Function Calls { #other-asynchronous-function-calls }

As the testing function is now asynchronous, you can now also call (and `await`) other `async` functions apart from sending requests to your FastAPI application in your tests, exactly as you would call them anywhere else in your code.

-# Behind a Proxy

+# Behind a Proxy { #behind-a-proxy }

In some situations, you might need to use a **proxy** server like Traefik or Nginx with a configuration that adds an extra path prefix that is not seen by your application.

And it's also used internally when mounting sub-applications.

-## Proxy with a stripped path prefix

+## Proxy with a stripped path prefix { #proxy-with-a-stripped-path-prefix }

Having a proxy with a stripped path prefix, in this case, means that you could declare a path at `/app` in your code, but then, you add a layer on top (the proxy) that would put your **FastAPI** application under a path like `/api/v1`.

In this example, the "Proxy" could be something like **Traefik**. And the server would be something like FastAPI CLI with **Uvicorn**, running your FastAPI application.

-### Providing the `root_path`

+### Providing the `root_path` { #providing-the-root-path }

To achieve this, you can use the command line option `--root-path` like:

///

-### Checking the current `root_path`

+### Checking the current `root_path` { #checking-the-current-root-path }

You can get the current `root_path` used by your application for each request, it is part of the `scope` dictionary (that's part of the ASGI spec).

}

```

-### Setting the `root_path` in the FastAPI app

+### Setting the `root_path` in the FastAPI app { #setting-the-root-path-in-the-fastapi-app }

Alternatively, if you don't have a way to provide a command line option like `--root-path` or equivalent, you can set the `root_path` parameter when creating your FastAPI app:

Passing the `root_path` to `FastAPI` would be the equivalent of passing the `--root-path` command line option to Uvicorn or Hypercorn.

-### About `root_path`

+### About `root_path` { #about-root-path }

Keep in mind that the server (Uvicorn) won't use that `root_path` for anything else than passing it to the app.

Uvicorn will expect the proxy to access Uvicorn at `http://127.0.0.1:8000/app`, and then it would be the proxy's responsibility to add the extra `/api/v1` prefix on top.

-## About proxies with a stripped path prefix

+## About proxies with a stripped path prefix { #about-proxies-with-a-stripped-path-prefix }

Keep in mind that a proxy with stripped path prefix is only one of the ways to configure it.

In a case like that (without a stripped path prefix), the proxy would listen on something like `https://myawesomeapp.com`, and then if the browser goes to `https://myawesomeapp.com/api/v1/app` and your server (e.g. Uvicorn) listens on `http://127.0.0.1:8000` the proxy (without a stripped path prefix) would access Uvicorn at the same path: `http://127.0.0.1:8000/api/v1/app`.

-## Testing locally with Traefik

+## Testing locally with Traefik { #testing-locally-with-traefik }

You can easily run the experiment locally with a stripped path prefix using <a href="https://docs.traefik.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Traefik</a>.

</div>

-### Check the responses

+### Check the responses { #check-the-responses }

Now, if you go to the URL with the port for Uvicorn: <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/app" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/app</a>, you will see the normal response:

That demonstrates how the Proxy (Traefik) uses the path prefix and how the server (Uvicorn) uses the `root_path` from the option `--root-path`.

-### Check the docs UI

+### Check the docs UI { #check-the-docs-ui }

But here's the fun part. ✨

This is because FastAPI uses this `root_path` to create the default `server` in OpenAPI with the URL provided by `root_path`.

-## Additional servers

+## Additional servers { #additional-servers }

/// warning

///

-### Disable automatic server from `root_path`

+### Disable automatic server from `root_path` { #disable-automatic-server-from-root-path }

If you don't want **FastAPI** to include an automatic server using the `root_path`, you can use the parameter `root_path_in_servers=False`:

and then it won't include it in the OpenAPI schema.

-## Mounting a sub-application

+## Mounting a sub-application { #mounting-a-sub-application }

If you need to mount a sub-application (as described in [Sub Applications - Mounts](sub-applications.md){.internal-link target=_blank}) while also using a proxy with `root_path`, you can do it normally, as you would expect.

-# Custom Response - HTML, Stream, File, others

+# Custom Response - HTML, Stream, File, others { #custom-response-html-stream-file-others }

By default, **FastAPI** will return the responses using `JSONResponse`.

///

-## Use `ORJSONResponse`

+## Use `ORJSONResponse` { #use-orjsonresponse }

For example, if you are squeezing performance, you can install and use <a href="https://github.com/ijl/orjson" class="external-link" target="_blank">`orjson`</a> and set the response to be `ORJSONResponse`.

///

-## HTML Response

+## HTML Response { #html-response }

To return a response with HTML directly from **FastAPI**, use `HTMLResponse`.

///

-### Return a `Response`

+### Return a `Response` { #return-a-response }

As seen in [Return a Response directly](response-directly.md){.internal-link target=_blank}, you can also override the response directly in your *path operation*, by returning it.

///

-### Document in OpenAPI and override `Response`

+### Document in OpenAPI and override `Response` { #document-in-openapi-and-override-response }

If you want to override the response from inside of the function but at the same time document the "media type" in OpenAPI, you can use the `response_class` parameter AND return a `Response` object.

The `response_class` will then be used only to document the OpenAPI *path operation*, but your `Response` will be used as is.

-#### Return an `HTMLResponse` directly

+#### Return an `HTMLResponse` directly { #return-an-htmlresponse-directly }

For example, it could be something like:

<img src="/img/tutorial/custom-response/image01.png">

-## Available responses

+## Available responses { #available-responses }

Here are some of the available responses.

///

-### `Response`

+### `Response` { #response }

The main `Response` class, all the other responses inherit from it.

{* ../../docs_src/response_directly/tutorial002.py hl[1,18] *}

-### `HTMLResponse`

+### `HTMLResponse` { #htmlresponse }

Takes some text or bytes and returns an HTML response, as you read above.

-### `PlainTextResponse`

+### `PlainTextResponse` { #plaintextresponse }

Takes some text or bytes and returns a plain text response.

{* ../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial005.py hl[2,7,9] *}

-### `JSONResponse`

+### `JSONResponse` { #jsonresponse }

Takes some data and returns an `application/json` encoded response.

This is the default response used in **FastAPI**, as you read above.

-### `ORJSONResponse`

+### `ORJSONResponse` { #orjsonresponse }

A fast alternative JSON response using <a href="https://github.com/ijl/orjson" class="external-link" target="_blank">`orjson`</a>, as you read above.

///

-### `UJSONResponse`

+### `UJSONResponse` { #ujsonresponse }

An alternative JSON response using <a href="https://github.com/ultrajson/ultrajson" class="external-link" target="_blank">`ujson`</a>.

///

-### `RedirectResponse`

+### `RedirectResponse` { #redirectresponse }

Returns an HTTP redirect. Uses a 307 status code (Temporary Redirect) by default.

{* ../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial006c.py hl[2,7,9] *}

-### `StreamingResponse`

+### `StreamingResponse` { #streamingresponse }

Takes an async generator or a normal generator/iterator and streams the response body.

{* ../../docs_src/custom_response/tutorial007.py hl[2,14] *}

-#### Using `StreamingResponse` with file-like objects

+#### Using `StreamingResponse` with file-like objects { #using-streamingresponse-with-file-like-objects }

If you have a file-like object (e.g. the object returned by `open()`), you can create a generator function to iterate over that file-like object.

///

-### `FileResponse`

+### `FileResponse` { #fileresponse }

Asynchronously streams a file as the response.

In this case, you can return the file path directly from your *path operation* function.

-## Custom response class

+## Custom response class { #custom-response-class }

You can create your own custom response class, inheriting from `Response` and using it.

Of course, you will probably find much better ways to take advantage of this than formatting JSON. 😉

-## Default response class

+## Default response class { #default-response-class }

When creating a **FastAPI** class instance or an `APIRouter` you can specify which response class to use by default.

///

-## Additional documentation

+## Additional documentation { #additional-documentation }

You can also declare the media type and many other details in OpenAPI using `responses`: [Additional Responses in OpenAPI](additional-responses.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

-# Using Dataclasses

+# Using Dataclasses { #using-dataclasses }

FastAPI is built on top of **Pydantic**, and I have been showing you how to use Pydantic models to declare requests and responses.

///

-## Dataclasses in `response_model`

+## Dataclasses in `response_model` { #dataclasses-in-response-model }

You can also use `dataclasses` in the `response_model` parameter:

<img src="/img/tutorial/dataclasses/image01.png">

-## Dataclasses in Nested Data Structures

+## Dataclasses in Nested Data Structures { #dataclasses-in-nested-data-structures }

You can also combine `dataclasses` with other type annotations to make nested data structures.

Check the in-code annotation tips above to see more specific details.

-## Learn More

+## Learn More { #learn-more }

You can also combine `dataclasses` with other Pydantic models, inherit from them, include them in your own models, etc.

To learn more, check the <a href="https://docs.pydantic.dev/latest/concepts/dataclasses/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Pydantic docs about dataclasses</a>.

-## Version

+## Version { #version }

This is available since FastAPI version `0.67.0`. 🔖

-# Lifespan Events

+# Lifespan Events { #lifespan-events }

You can define logic (code) that should be executed before the application **starts up**. This means that this code will be executed **once**, **before** the application **starts receiving requests**.

This can be very useful for setting up **resources** that you need to use for the whole app, and that are **shared** among requests, and/or that you need to **clean up** afterwards. For example, a database connection pool, or loading a shared machine learning model.

-## Use Case

+## Use Case { #use-case }

Let's start with an example **use case** and then see how to solve it with this.

That's what we'll solve, let's load the model before the requests are handled, but only right before the application starts receiving requests, not while the code is being loaded.

-## Lifespan

+## Lifespan { #lifespan }

You can define this *startup* and *shutdown* logic using the `lifespan` parameter of the `FastAPI` app, and a "context manager" (I'll show you what that is in a second).

///

-### Lifespan function

+### Lifespan function { #lifespan-function }

The first thing to notice, is that we are defining an async function with `yield`. This is very similar to Dependencies with `yield`.

And the part after the `yield` will be executed **after** the application has finished.

-### Async Context Manager

+### Async Context Manager { #async-context-manager }

If you check, the function is decorated with an `@asynccontextmanager`.

{* ../../docs_src/events/tutorial003.py hl[22] *}

-## Alternative Events (deprecated)

+## Alternative Events (deprecated) { #alternative-events-deprecated }

/// warning

These functions can be declared with `async def` or normal `def`.

-### `startup` event

+### `startup` event { #startup-event }

To add a function that should be run before the application starts, declare it with the event `"startup"`:

And your application won't start receiving requests until all the `startup` event handlers have completed.

-### `shutdown` event

+### `shutdown` event { #shutdown-event }

To add a function that should be run when the application is shutting down, declare it with the event `"shutdown"`:

///

-### `startup` and `shutdown` together

+### `startup` and `shutdown` together { #startup-and-shutdown-together }

There's a high chance that the logic for your *startup* and *shutdown* is connected, you might want to start something and then finish it, acquire a resource and then release it, etc.

Because of that, it's now recommended to instead use the `lifespan` as explained above.

-## Technical Details

+## Technical Details { #technical-details }

Just a technical detail for the curious nerds. 🤓

///

-## Sub Applications

+## Sub Applications { #sub-applications }

🚨 Keep in mind that these lifespan events (startup and shutdown) will only be executed for the main application, not for [Sub Applications - Mounts](sub-applications.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

-# Generating SDKs

+# Generating SDKs { #generating-sdks }

Because **FastAPI** is based on the **OpenAPI** specification, its APIs can be described in a standard format that many tools understand.

In this guide, you'll learn how to generate a **TypeScript SDK** for your FastAPI backend.

-## Open Source SDK Generators

+## Open Source SDK Generators { #open-source-sdk-generators }

A versatile option is the <a href="https://openapi-generator.tech/" class="external-link" target="_blank">OpenAPI Generator</a>, which supports **many programming languages** and can generate SDKs from your OpenAPI specification.

///

-## SDK Generators from FastAPI Sponsors

+## SDK Generators from FastAPI Sponsors { #sdk-generators-from-fastapi-sponsors }

This section highlights **venture-backed** and **company-supported** solutions from companies that sponsor FastAPI. These products provide **additional features** and **integrations** on top of high-quality generated SDKs.

Some of these solutions may also be open source or offer free tiers, so you can try them without a financial commitment. Other commercial SDK generators are available and can be found online. 🤓

-## Create a TypeScript SDK

+## Create a TypeScript SDK { #create-a-typescript-sdk }

Let's start with a simple FastAPI application:

Notice that the *path operations* define the models they use for request payload and response payload, using the models `Item` and `ResponseMessage`.

-### API Docs

+### API Docs { #api-docs }

If you go to `/docs`, you will see that it has the **schemas** for the data to be sent in requests and received in responses:

That same information from the models that is included in OpenAPI is what can be used to **generate the client code**.

-### Hey API

+### Hey API { #hey-api }

Once we have a FastAPI app with the models, we can use Hey API to generate a TypeScript client. The fastest way to do that is via npx.

You can learn how to <a href="https://heyapi.dev/openapi-ts/get-started" class="external-link" target="_blank">install `@hey-api/openapi-ts`</a> and read about the <a href="https://heyapi.dev/openapi-ts/output" class="external-link" target="_blank">generated output</a> on their website.

-### Using the SDK

+### Using the SDK { #using-the-sdk }

Now you can import and use the client code. It could look like this, notice that you get autocompletion for the methods:

<img src="/img/tutorial/generate-clients/image05.png">

-## FastAPI App with Tags

+## FastAPI App with Tags { #fastapi-app-with-tags }

In many cases, your FastAPI app will be bigger, and you will probably use tags to separate different groups of *path operations*.

{* ../../docs_src/generate_clients/tutorial002_py39.py hl[21,26,34] *}

-### Generate a TypeScript Client with Tags

+### Generate a TypeScript Client with Tags { #generate-a-typescript-client-with-tags }

If you generate a client for a FastAPI app using tags, it will normally also separate the client code based on the tags.

* `ItemsService`

* `UsersService`

-### Client Method Names

+### Client Method Names { #client-method-names }

Right now, the generated method names like `createItemItemsPost` don't look very clean:

But I'll show you how to improve that next. 🤓

-## Custom Operation IDs and Better Method Names

+## Custom Operation IDs and Better Method Names { #custom-operation-ids-and-better-method-names }

You can **modify** the way these operation IDs are **generated** to make them simpler and have **simpler method names** in the clients.

For example, you could make sure that each *path operation* has a tag, and then generate the operation ID based on the **tag** and the *path operation* **name** (the function name).

-### Custom Generate Unique ID Function

+### Custom Generate Unique ID Function { #custom-generate-unique-id-function }

FastAPI uses a **unique ID** for each *path operation*, which is used for the **operation ID** and also for the names of any needed custom models, for requests or responses.

{* ../../docs_src/generate_clients/tutorial003_py39.py hl[6:7,10] *}

-### Generate a TypeScript Client with Custom Operation IDs

+### Generate a TypeScript Client with Custom Operation IDs { #generate-a-typescript-client-with-custom-operation-ids }

Now, if you generate the client again, you will see that it has the improved method names:

As you see, the method names now have the tag and then the function name, now they don't include information from the URL path and the HTTP operation.

-### Preprocess the OpenAPI Specification for the Client Generator

+### Preprocess the OpenAPI Specification for the Client Generator { #preprocess-the-openapi-specification-for-the-client-generator }

The generated code still has some **duplicated information**.

With that, the operation IDs would be renamed from things like `items-get_items` to just `get_items`, that way the client generator can generate simpler method names.

-### Generate a TypeScript Client with the Preprocessed OpenAPI

+### Generate a TypeScript Client with the Preprocessed OpenAPI { #generate-a-typescript-client-with-the-preprocessed-openapi }

Since the end result is now in an `openapi.json` file, you need to update your input location:

<img src="/img/tutorial/generate-clients/image08.png">

-## Benefits

+## Benefits { #benefits }

When using the automatically generated clients, you would get **autocompletion** for:

-# Advanced User Guide

+# Advanced User Guide { #advanced-user-guide }

-## Additional Features

+## Additional Features { #additional-features }

The main [Tutorial - User Guide](../tutorial/index.md){.internal-link target=_blank} should be enough to give you a tour through all the main features of **FastAPI**.

///

-## Read the Tutorial first

+## Read the Tutorial first { #read-the-tutorial-first }

You could still use most of the features in **FastAPI** with the knowledge from the main [Tutorial - User Guide](../tutorial/index.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

-# Advanced Middleware

+# Advanced Middleware { #advanced-middleware }

In the main tutorial you read how to add [Custom Middleware](../tutorial/middleware.md){.internal-link target=_blank} to your application.

In this section we'll see how to use other middlewares.

-## Adding ASGI middlewares

+## Adding ASGI middlewares { #adding-asgi-middlewares }

As **FastAPI** is based on Starlette and implements the <abbr title="Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface">ASGI</abbr> specification, you can use any ASGI middleware.

`app.add_middleware()` receives a middleware class as the first argument and any additional arguments to be passed to the middleware.

-## Integrated middlewares

+## Integrated middlewares { #integrated-middlewares }

**FastAPI** includes several middlewares for common use cases, we'll see next how to use them.

///

-## `HTTPSRedirectMiddleware`

+## `HTTPSRedirectMiddleware` { #httpsredirectmiddleware }

Enforces that all incoming requests must either be `https` or `wss`.

{* ../../docs_src/advanced_middleware/tutorial001.py hl[2,6] *}

-## `TrustedHostMiddleware`

+## `TrustedHostMiddleware` { #trustedhostmiddleware }

Enforces that all incoming requests have a correctly set `Host` header, in order to guard against HTTP Host Header attacks.

If an incoming request does not validate correctly then a `400` response will be sent.

-## `GZipMiddleware`

+## `GZipMiddleware` { #gzipmiddleware }

Handles GZip responses for any request that includes `"gzip"` in the `Accept-Encoding` header.

* `minimum_size` - Do not GZip responses that are smaller than this minimum size in bytes. Defaults to `500`.

* `compresslevel` - Used during GZip compression. It is an integer ranging from 1 to 9. Defaults to `9`. Lower value results in faster compression but larger file sizes, while higher value results in slower compression but smaller file sizes.

-## Other middlewares

+## Other middlewares { #other-middlewares }

There are many other ASGI middlewares.

-# OpenAPI Callbacks

+# OpenAPI Callbacks { #openapi-callbacks }

You could create an API with a *path operation* that could trigger a request to an *external API* created by someone else (probably the same developer that would be *using* your API).

In this case, you could want to document how that external API *should* look like. What *path operation* it should have, what body it should expect, what response it should return, etc.

-## An app with callbacks

+## An app with callbacks { #an-app-with-callbacks }

Let's see all this with an example.

* Send a notification back to the API user (the external developer).

* This will be done by sending a POST request (from *your API*) to some *external API* provided by that external developer (this is the "callback").

-## The normal **FastAPI** app

+## The normal **FastAPI** app { #the-normal-fastapi-app }

Let's first see how the normal API app would look like before adding the callback.

The only new thing is the `callbacks=invoices_callback_router.routes` as an argument to the *path operation decorator*. We'll see what that is next.

-## Documenting the callback

+## Documenting the callback { #documenting-the-callback }

The actual callback code will depend heavily on your own API app.

///

-## Write the callback documentation code

+## Write the callback documentation code { #write-the-callback-documentation-code }

This code won't be executed in your app, we only need it to *document* how that *external API* should look like.

///

-### Create a callback `APIRouter`

+### Create a callback `APIRouter` { #create-a-callback-apirouter }

First create a new `APIRouter` that will contain one or more callbacks.

{* ../../docs_src/openapi_callbacks/tutorial001.py hl[3,25] *}

-### Create the callback *path operation*

+### Create the callback *path operation* { #create-the-callback-path-operation }

To create the callback *path operation* use the same `APIRouter` you created above.

* It doesn't need to have any actual code, because your app will never call this code. It's only used to document the *external API*. So, the function could just have `pass`.

* The *path* can contain an <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification/blob/master/versions/3.1.0.md#key-expression" class="external-link" target="_blank">OpenAPI 3 expression</a> (see more below) where it can use variables with parameters and parts of the original request sent to *your API*.

-### The callback path expression

+### The callback path expression { #the-callback-path-expression }

The callback *path* can have an <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification/blob/master/versions/3.1.0.md#key-expression" class="external-link" target="_blank">OpenAPI 3 expression</a> that can contain parts of the original request sent to *your API*.

///

-### Add the callback router

+### Add the callback router { #add-the-callback-router }

At this point you have the *callback path operation(s)* needed (the one(s) that the *external developer* should implement in the *external API*) in the callback router you created above.

///

-### Check the docs

+### Check the docs { #check-the-docs }

Now you can start your app and go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

-# OpenAPI Webhooks

+# OpenAPI Webhooks { #openapi-webhooks }

There are cases where you want to tell your API **users** that your app could call *their* app (sending a request) with some data, normally to **notify** of some type of **event**.

This is normally called a **webhook**.

-## Webhooks steps

+## Webhooks steps { #webhooks-steps }

The process normally is that **you define** in your code what is the message that you will send, the **body of the request**.

All the **logic** about how to register the URLs for webhooks and the code to actually send those requests is up to you. You write it however you want to in **your own code**.

-## Documenting webhooks with **FastAPI** and OpenAPI

+## Documenting webhooks with **FastAPI** and OpenAPI { #documenting-webhooks-with-fastapi-and-openapi }

With **FastAPI**, using OpenAPI, you can define the names of these webhooks, the types of HTTP operations that your app can send (e.g. `POST`, `PUT`, etc.) and the request **bodies** that your app would send.

///

-## An app with webhooks

+## An app with webhooks { #an-app-with-webhooks }

When you create a **FastAPI** application, there is a `webhooks` attribute that you can use to define *webhooks*, the same way you would define *path operations*, for example with `@app.webhooks.post()`.

This is because it is expected that **your users** would define the actual **URL path** where they want to receive the webhook request in some other way (e.g. a web dashboard).

-### Check the docs

+### Check the docs { #check-the-docs }

Now you can start your app and go to <a href="http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs" class="external-link" target="_blank">http://127.0.0.1:8000/docs</a>.

-# Path Operation Advanced Configuration

+# Path Operation Advanced Configuration { #path-operation-advanced-configuration }

-## OpenAPI operationId

+## OpenAPI operationId { #openapi-operationid }

/// warning

{* ../../docs_src/path_operation_advanced_configuration/tutorial001.py hl[6] *}

-### Using the *path operation function* name as the operationId

+### Using the *path operation function* name as the operationId { #using-the-path-operation-function-name-as-the-operationid }

If you want to use your APIs' function names as `operationId`s, you can iterate over all of them and override each *path operation's* `operation_id` using their `APIRoute.name`.

///

-## Exclude from OpenAPI

+## Exclude from OpenAPI { #exclude-from-openapi }

To exclude a *path operation* from the generated OpenAPI schema (and thus, from the automatic documentation systems), use the parameter `include_in_schema` and set it to `False`:

{* ../../docs_src/path_operation_advanced_configuration/tutorial003.py hl[6] *}

-## Advanced description from docstring

+## Advanced description from docstring { #advanced-description-from-docstring }

You can limit the lines used from the docstring of a *path operation function* for OpenAPI.

{* ../../docs_src/path_operation_advanced_configuration/tutorial004.py hl[19:29] *}

-## Additional Responses

+## Additional Responses { #additional-responses }

You probably have seen how to declare the `response_model` and `status_code` for a *path operation*.

There's a whole chapter here in the documentation about it, you can read it at [Additional Responses in OpenAPI](additional-responses.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

-## OpenAPI Extra

+## OpenAPI Extra { #openapi-extra }

When you declare a *path operation* in your application, **FastAPI** automatically generates the relevant metadata about that *path operation* to be included in the OpenAPI schema.

You can extend the OpenAPI schema for a *path operation* using the parameter `openapi_extra`.

-### OpenAPI Extensions

+### OpenAPI Extensions { #openapi-extensions }

This `openapi_extra` can be helpful, for example, to declare [OpenAPI Extensions](https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification/blob/main/versions/3.0.3.md#specificationExtensions):

}

```

-### Custom OpenAPI *path operation* schema

+### Custom OpenAPI *path operation* schema { #custom-openapi-path-operation-schema }

The dictionary in `openapi_extra` will be deeply merged with the automatically generated OpenAPI schema for the *path operation*.

Nevertheless, we can declare the expected schema for the request body.

-### Custom OpenAPI content type

+### Custom OpenAPI content type { #custom-openapi-content-type }

Using this same trick, you could use a Pydantic model to define the JSON Schema that is then included in the custom OpenAPI schema section for the *path operation*.

-# Response - Change Status Code

+# Response - Change Status Code { #response-change-status-code }

You probably read before that you can set a default [Response Status Code](../tutorial/response-status-code.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

But in some cases you need to return a different status code than the default.

-## Use case

+## Use case { #use-case }

For example, imagine that you want to return an HTTP status code of "OK" `200` by default.

For those cases, you can use a `Response` parameter.

-## Use a `Response` parameter

+## Use a `Response` parameter { #use-a-response-parameter }

You can declare a parameter of type `Response` in your *path operation function* (as you can do for cookies and headers).

-# Response Cookies

+# Response Cookies { #response-cookies }

-## Use a `Response` parameter

+## Use a `Response` parameter { #use-a-response-parameter }

You can declare a parameter of type `Response` in your *path operation function*.

You can also declare the `Response` parameter in dependencies, and set cookies (and headers) in them.

-## Return a `Response` directly

+## Return a `Response` directly { #return-a-response-directly }

You can also create cookies when returning a `Response` directly in your code.

///

-### More info

+### More info { #more-info }

/// note | Technical Details

-# Return a Response Directly

+# Return a Response Directly { #return-a-response-directly }

When you create a **FastAPI** *path operation* you can normally return any data from it: a `dict`, a `list`, a Pydantic model, a database model, etc.

It might be useful, for example, to return custom headers or cookies.

-## Return a `Response`

+## Return a `Response` { #return-a-response }

In fact, you can return any `Response` or any sub-class of it.

This gives you a lot of flexibility. You can return any data type, override any data declaration or validation, etc.

-## Using the `jsonable_encoder` in a `Response`

+## Using the `jsonable_encoder` in a `Response` { #using-the-jsonable-encoder-in-a-response }

Because **FastAPI** doesn't make any changes to a `Response` you return, you have to make sure its contents are ready for it.

///

-## Returning a custom `Response`

+## Returning a custom `Response` { #returning-a-custom-response }

The example above shows all the parts you need, but it's not very useful yet, as you could have just returned the `item` directly, and **FastAPI** would put it in a `JSONResponse` for you, converting it to a `dict`, etc. All that by default.

{* ../../docs_src/response_directly/tutorial002.py hl[1,18] *}

-## Notes

+## Notes { #notes }

When you return a `Response` directly its data is not validated, converted (serialized), or documented automatically.

-# Response Headers

+# Response Headers { #response-headers }

-## Use a `Response` parameter

+## Use a `Response` parameter { #use-a-response-parameter }

You can declare a parameter of type `Response` in your *path operation function* (as you can do for cookies).

You can also declare the `Response` parameter in dependencies, and set headers (and cookies) in them.

-## Return a `Response` directly

+## Return a `Response` directly { #return-a-response-directly }

You can also add headers when you return a `Response` directly.

///

-## Custom Headers

+## Custom Headers { #custom-headers }

Keep in mind that custom proprietary headers can be added <a href="https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Headers" class="external-link" target="_blank">using the 'X-' prefix</a>.

-# HTTP Basic Auth

+# HTTP Basic Auth { #http-basic-auth }

For the simplest cases, you can use HTTP Basic Auth.

Then, when you type that username and password, the browser sends them in the header automatically.

-## Simple HTTP Basic Auth

+## Simple HTTP Basic Auth { #simple-http-basic-auth }

* Import `HTTPBasic` and `HTTPBasicCredentials`.

* Create a "`security` scheme" using `HTTPBasic`.

<img src="/img/tutorial/security/image12.png">

-## Check the username

+## Check the username { #check-the-username }

Here's a more complete example.

But by using the `secrets.compare_digest()` it will be secure against a type of attacks called "timing attacks".

-### Timing Attacks

+### Timing Attacks { #timing-attacks }

But what's a "timing attack"?

Python will have to compare the whole `stanleyjobso` in both `stanleyjobsox` and `stanleyjobson` before realizing that both strings are not the same. So it will take some extra microseconds to reply back "Incorrect username or password".

-#### The time to answer helps the attackers

+#### The time to answer helps the attackers { #the-time-to-answer-helps-the-attackers }

At that point, by noticing that the server took some microseconds longer to send the "Incorrect username or password" response, the attackers will know that they got _something_ right, some of the initial letters were right.

And then they can try again knowing that it's probably something more similar to `stanleyjobsox` than to `johndoe`.

-#### A "professional" attack

+#### A "professional" attack { #a-professional-attack }

Of course, the attackers would not try all this by hand, they would write a program to do it, possibly with thousands or millions of tests per second. And they would get just one extra correct letter at a time.

But doing that, in some minutes or hours the attackers would have guessed the correct username and password, with the "help" of our application, just using the time taken to answer.

-#### Fix it with `secrets.compare_digest()`

+#### Fix it with `secrets.compare_digest()` { #fix-it-with-secrets-compare-digest }

But in our code we are actually using `secrets.compare_digest()`.

That way, using `secrets.compare_digest()` in your application code, it will be safe against this whole range of security attacks.

-### Return the error

+### Return the error { #return-the-error }

After detecting that the credentials are incorrect, return an `HTTPException` with a status code 401 (the same returned when no credentials are provided) and add the header `WWW-Authenticate` to make the browser show the login prompt again:

-# Advanced Security

+# Advanced Security { #advanced-security }

-## Additional Features

+## Additional Features { #additional-features }

There are some extra features to handle security apart from the ones covered in the [Tutorial - User Guide: Security](../../tutorial/security/index.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

///

-## Read the Tutorial first

+## Read the Tutorial first { #read-the-tutorial-first }

The next sections assume you already read the main [Tutorial - User Guide: Security](../../tutorial/security/index.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

-# OAuth2 scopes

+# OAuth2 scopes { #oauth2-scopes }

You can use OAuth2 scopes directly with **FastAPI**, they are integrated to work seamlessly.

///

-## OAuth2 scopes and OpenAPI

+## OAuth2 scopes and OpenAPI { #oauth2-scopes-and-openapi }

The OAuth2 specification defines "scopes" as a list of strings separated by spaces.

///

-## Global view

+## Global view { #global-view }

First, let's quickly see the parts that change from the examples in the main **Tutorial - User Guide** for [OAuth2 with Password (and hashing), Bearer with JWT tokens](../../tutorial/security/oauth2-jwt.md){.internal-link target=_blank}. Now using OAuth2 scopes:

Now let's review those changes step by step.

-## OAuth2 Security scheme

+## OAuth2 Security scheme { #oauth2-security-scheme }

The first change is that now we are declaring the OAuth2 security scheme with two available scopes, `me` and `items`.

<img src="/img/tutorial/security/image11.png">

-## JWT token with scopes

+## JWT token with scopes { #jwt-token-with-scopes }

Now, modify the token *path operation* to return the scopes requested.

{* ../../docs_src/security/tutorial005_an_py310.py hl[156] *}

-## Declare scopes in *path operations* and dependencies

+## Declare scopes in *path operations* and dependencies { #declare-scopes-in-path-operations-and-dependencies }

Now we declare that the *path operation* for `/users/me/items/` requires the scope `items`.

///

-## Use `SecurityScopes`

+## Use `SecurityScopes` { #use-securityscopes }

Now update the dependency `get_current_user`.

{* ../../docs_src/security/tutorial005_an_py310.py hl[9,106] *}

-## Use the `scopes`

+## Use the `scopes` { #use-the-scopes }

The parameter `security_scopes` will be of type `SecurityScopes`.

{* ../../docs_src/security/tutorial005_an_py310.py hl[106,108:116] *}

-## Verify the `username` and data shape

+## Verify the `username` and data shape { #verify-the-username-and-data-shape }

We verify that we get a `username`, and extract the scopes.

{* ../../docs_src/security/tutorial005_an_py310.py hl[47,117:128] *}

-## Verify the `scopes`

+## Verify the `scopes` { #verify-the-scopes }

We now verify that all the scopes required, by this dependency and all the dependants (including *path operations*), are included in the scopes provided in the token received, otherwise raise an `HTTPException`.

{* ../../docs_src/security/tutorial005_an_py310.py hl[129:135] *}

-## Dependency tree and scopes

+## Dependency tree and scopes { #dependency-tree-and-scopes }

Let's review again this dependency tree and the scopes.

///

-## More details about `SecurityScopes`

+## More details about `SecurityScopes` { #more-details-about-securityscopes }

You can use `SecurityScopes` at any point, and in multiple places, it doesn't have to be at the "root" dependency.

They will be checked independently for each *path operation*.

-## Check it

+## Check it { #check-it }

If you open the API docs, you can authenticate and specify which scopes you want to authorize.

That's what would happen to a third party application that tried to access one of these *path operations* with a token provided by a user, depending on how many permissions the user gave the application.

-## About third party integrations

+## About third party integrations { #about-third-party-integrations }

In this example we are using the OAuth2 "password" flow.

**FastAPI** includes utilities for all these OAuth2 authentication flows in `fastapi.security.oauth2`.

-## `Security` in decorator `dependencies`

+## `Security` in decorator `dependencies` { #security-in-decorator-dependencies }

The same way you can define a `list` of `Depends` in the decorator's `dependencies` parameter (as explained in [Dependencies in path operation decorators](../../tutorial/dependencies/dependencies-in-path-operation-decorators.md){.internal-link target=_blank}), you could also use `Security` with `scopes` there.

-# Settings and Environment Variables

+# Settings and Environment Variables { #settings-and-environment-variables }

In many cases your application could need some external settings or configurations, for example secret keys, database credentials, credentials for email services, etc.

///

-## Types and validation

+## Types and validation { #types-and-validation }

These environment variables can only handle text strings, as they are external to Python and have to be compatible with other programs and the rest of the system (and even with different operating systems, as Linux, Windows, macOS).

That means that any value read in Python from an environment variable will be a `str`, and any conversion to a different type or any validation has to be done in code.

-## Pydantic `Settings`

+## Pydantic `Settings` { #pydantic-settings }

Fortunately, Pydantic provides a great utility to handle these settings coming from environment variables with <a href="https://docs.pydantic.dev/latest/concepts/pydantic_settings/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Pydantic: Settings management</a>.

-### Install `pydantic-settings`

+### Install `pydantic-settings` { #install-pydantic-settings }

First, make sure you create your [virtual environment](../virtual-environments.md){.internal-link target=_blank}, activate it, and then install the `pydantic-settings` package:

///

-### Create the `Settings` object

+### Create the `Settings` object { #create-the-settings-object }

Import `BaseSettings` from Pydantic and create a sub-class, very much like with a Pydantic model.

Next it will convert and validate the data. So, when you use that `settings` object, you will have data of the types you declared (e.g. `items_per_user` will be an `int`).

-### Use the `settings`

+### Use the `settings` { #use-the-settings }

Then you can use the new `settings` object in your application:

{* ../../docs_src/settings/tutorial001.py hl[18:20] *}

-### Run the server

+### Run the server { #run-the-server }

Next, you would run the server passing the configurations as environment variables, for example you could set an `ADMIN_EMAIL` and `APP_NAME` with:

And the `items_per_user` would keep its default value of `50`.

-## Settings in another module

+## Settings in another module { #settings-in-another-module }

You could put those settings in another module file as you saw in [Bigger Applications - Multiple Files](../tutorial/bigger-applications.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

///

-## Settings in a dependency

+## Settings in a dependency { #settings-in-a-dependency }

In some occasions it might be useful to provide the settings from a dependency, instead of having a global object with `settings` that is used everywhere.

This could be especially useful during testing, as it's very easy to override a dependency with your own custom settings.

-### The config file

+### The config file { #the-config-file }

Coming from the previous example, your `config.py` file could look like:

Notice that now we don't create a default instance `settings = Settings()`.

-### The main app file

+### The main app file { #the-main-app-file }

Now we create a dependency that returns a new `config.Settings()`.

{* ../../docs_src/settings/app02_an_py39/main.py hl[17,19:21] *}

-### Settings and testing

+### Settings and testing { #settings-and-testing }

Then it would be very easy to provide a different settings object during testing by creating a dependency override for `get_settings`:

Then we can test that it is used.

-## Reading a `.env` file

+## Reading a `.env` file { #reading-a-env-file }

If you have many settings that possibly change a lot, maybe in different environments, it might be useful to put them on a file and then read them from it as if they were environment variables.

///

-### The `.env` file

+### The `.env` file { #the-env-file }

You could have a `.env` file with:

APP_NAME="ChimichangApp"

```

-### Read settings from `.env`

+### Read settings from `.env` { #read-settings-from-env }

And then update your `config.py` with:

Here we define the config `env_file` inside of your Pydantic `Settings` class, and set the value to the filename with the dotenv file we want to use.

-### Creating the `Settings` only once with `lru_cache`

+### Creating the `Settings` only once with `lru_cache` { #creating-the-settings-only-once-with-lru-cache }

Reading a file from disk is normally a costly (slow) operation, so you probably want to do it only once and then reuse the same settings object, instead of reading it for each request.

Then for any subsequent call of `get_settings()` in the dependencies for the next requests, instead of executing the internal code of `get_settings()` and creating a new `Settings` object, it will return the same object that was returned on the first call, again and again.

-#### `lru_cache` Technical Details

+#### `lru_cache` Technical Details { #lru-cache-technical-details }

`@lru_cache` modifies the function it decorates to return the same value that was returned the first time, instead of computing it again, executing the code of the function every time.

`@lru_cache` is part of `functools` which is part of Python's standard library, you can read more about it in the <a href="https://docs.python.org/3/library/functools.html#functools.lru_cache" class="external-link" target="_blank">Python docs for `@lru_cache`</a>.

-## Recap

+## Recap { #recap }

You can use Pydantic Settings to handle the settings or configurations for your application, with all the power of Pydantic models.

-# Sub Applications - Mounts

+# Sub Applications - Mounts { #sub-applications-mounts }

If you need to have two independent FastAPI applications, with their own independent OpenAPI and their own docs UIs, you can have a main app and "mount" one (or more) sub-application(s).

-## Mounting a **FastAPI** application

+## Mounting a **FastAPI** application { #mounting-a-fastapi-application }

"Mounting" means adding a completely "independent" application in a specific path, that then takes care of handling everything under that path, with the _path operations_ declared in that sub-application.

-### Top-level application

+### Top-level application { #top-level-application }

First, create the main, top-level, **FastAPI** application, and its *path operations*:

{* ../../docs_src/sub_applications/tutorial001.py hl[3, 6:8] *}

-### Sub-application

+### Sub-application { #sub-application }

Then, create your sub-application, and its *path operations*.

{* ../../docs_src/sub_applications/tutorial001.py hl[11, 14:16] *}

-### Mount the sub-application

+### Mount the sub-application { #mount-the-sub-application }

In your top-level application, `app`, mount the sub-application, `subapi`.

{* ../../docs_src/sub_applications/tutorial001.py hl[11, 19] *}

-### Check the automatic API docs

+### Check the automatic API docs { #check-the-automatic-api-docs }

Now, run the `fastapi` command with your file:

If you try interacting with any of the two user interfaces, they will work correctly, because the browser will be able to talk to each specific app or sub-app.

-### Technical Details: `root_path`

+### Technical Details: `root_path` { #technical-details-root-path }

When you mount a sub-application as described above, FastAPI will take care of communicating the mount path for the sub-application using a mechanism from the ASGI specification called a `root_path`.

-# Templates

+# Templates { #templates }

You can use any template engine you want with **FastAPI**.

There are utilities to configure it easily that you can use directly in your **FastAPI** application (provided by Starlette).

-## Install dependencies

+## Install dependencies { #install-dependencies }

Make sure you create a [virtual environment](../virtual-environments.md){.internal-link target=_blank}, activate it, and install `jinja2`:

</div>

-## Using `Jinja2Templates`

+## Using `Jinja2Templates` { #using-jinja2templates }

* Import `Jinja2Templates`.

* Create a `templates` object that you can reuse later.

///

-## Writing templates

+## Writing templates { #writing-templates }

Then you can write a template at `templates/item.html` with, for example:

{!../../docs_src/templates/templates/item.html!}

```

-### Template Context Values

+### Template Context Values { #template-context-values }

In the HTML that contains:

Item ID: 42

```

-### Template `url_for` Arguments

+### Template `url_for` Arguments { #template-url-for-arguments }

You can also use `url_for()` inside of the template, it takes as arguments the same arguments that would be used by your *path operation function*.

<a href="/items/42">

```

-## Templates and static files

+## Templates and static files { #templates-and-static-files }

You can also use `url_for()` inside of the template, and use it, for example, with the `StaticFiles` you mounted with the `name="static"`.

And because you are using `StaticFiles`, that CSS file would be served automatically by your **FastAPI** application at the URL `/static/styles.css`.

-## More details

+## More details { #more-details }

For more details, including how to test templates, check <a href="https://www.starlette.io/templates/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Starlette's docs on templates</a>.

-# Testing Dependencies with Overrides

+# Testing Dependencies with Overrides { #testing-dependencies-with-overrides }

-## Overriding dependencies during testing

+## Overriding dependencies during testing { #overriding-dependencies-during-testing }

There are some scenarios where you might want to override a dependency during testing.

Instead, you want to provide a different dependency that will be used only during tests (possibly only some specific tests), and will provide a value that can be used where the value of the original dependency was used.

-### Use cases: external service

+### Use cases: external service { #use-cases-external-service }

An example could be that you have an external authentication provider that you need to call.

In this case, you can override the dependency that calls that provider, and use a custom dependency that returns a mock user, only for your tests.

-### Use the `app.dependency_overrides` attribute

+### Use the `app.dependency_overrides` attribute { #use-the-app-dependency-overrides-attribute }

For these cases, your **FastAPI** application has an attribute `app.dependency_overrides`, it is a simple `dict`.

-# Testing Events: startup - shutdown

+# Testing Events: startup - shutdown { #testing-events-startup-shutdown }

When you need your event handlers (`startup` and `shutdown`) to run in your tests, you can use the `TestClient` with a `with` statement:

-# Testing WebSockets

+# Testing WebSockets { #testing-websockets }

You can use the same `TestClient` to test WebSockets.

-# Using the Request Directly

+# Using the Request Directly { #using-the-request-directly }

Up to now, you have been declaring the parts of the request that you need with their types.

But there are situations where you might need to access the `Request` object directly.

-## Details about the `Request` object

+## Details about the `Request` object { #details-about-the-request-object }

As **FastAPI** is actually **Starlette** underneath, with a layer of several tools on top, you can use Starlette's <a href="https://www.starlette.io/requests/" class="external-link" target="_blank">`Request`</a> object directly when you need to.

But there are specific cases where it's useful to get the `Request` object.

-## Use the `Request` object directly

+## Use the `Request` object directly { #use-the-request-object-directly }

Let's imagine you want to get the client's IP address/host inside of your *path operation function*.

///

-## `Request` documentation

+## `Request` documentation { #request-documentation }

You can read more details about the <a href="https://www.starlette.io/requests/" class="external-link" target="_blank">`Request` object in the official Starlette documentation site</a>.

-# WebSockets

+# WebSockets { #websockets }

You can use <a href="https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/WebSockets_API" class="external-link" target="_blank">WebSockets</a> with **FastAPI**.

-## Install `WebSockets`

+## Install `WebSockets` { #install-websockets }

Make sure you create a [virtual environment](../virtual-environments.md){.internal-link target=_blank}, activate it, and install `websockets`:

</div>

-## WebSockets client

+## WebSockets client { #websockets-client }

-### In production

+### In production { #in-production }

In your production system, you probably have a frontend created with a modern framework like React, Vue.js or Angular.

{* ../../docs_src/websockets/tutorial001.py hl[2,6:38,41:43] *}

-## Create a `websocket`

+## Create a `websocket` { #create-a-websocket }

In your **FastAPI** application, create a `websocket`:

///

-## Await for messages and send messages

+## Await for messages and send messages { #await-for-messages-and-send-messages }

In your WebSocket route you can `await` for messages and send messages.

You can receive and send binary, text, and JSON data.

-## Try it

+## Try it { #try-it }

If your file is named `main.py`, run your application with:

And all of them will use the same WebSocket connection.

-## Using `Depends` and others

+## Using `Depends` and others { #using-depends-and-others }

In WebSocket endpoints you can import from `fastapi` and use:

///

-### Try the WebSockets with dependencies

+### Try the WebSockets with dependencies { #try-the-websockets-with-dependencies }

If your file is named `main.py`, run your application with:

<img src="/img/tutorial/websockets/image05.png">

-## Handling disconnections and multiple clients

+## Handling disconnections and multiple clients { #handling-disconnections-and-multiple-clients }

When a WebSocket connection is closed, the `await websocket.receive_text()` will raise a `WebSocketDisconnect` exception, which you can then catch and handle like in this example.

///

-## More info

+## More info { #more-info }

To learn more about the options, check Starlette's documentation for:

-# Including WSGI - Flask, Django, others

+# Including WSGI - Flask, Django, others { #including-wsgi-flask-django-others }

You can mount WSGI applications as you saw with [Sub Applications - Mounts](sub-applications.md){.internal-link target=_blank}, [Behind a Proxy](behind-a-proxy.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

For that, you can use the `WSGIMiddleware` and use it to wrap your WSGI application, for example, Flask, Django, etc.

-## Using `WSGIMiddleware`

+## Using `WSGIMiddleware` { #using-wsgimiddleware }

You need to import `WSGIMiddleware`.

{* ../../docs_src/wsgi/tutorial001.py hl[2:3,3] *}

-## Check it

+## Check it { #check-it }

Now, every request under the path `/v1/` will be handled by the Flask application.

-# Alternatives, Inspiration and Comparisons

+# Alternatives, Inspiration and Comparisons { #alternatives-inspiration-and-comparisons }

What inspired **FastAPI**, how it compares to alternatives and what it learned from them.

-## Intro

+## Intro { #intro }

**FastAPI** wouldn't exist if not for the previous work of others.

But at some point, there was no other option than creating something that provided all these features, taking the best ideas from previous tools, and combining them in the best way possible, using language features that weren't even available before (Python 3.6+ type hints).

-## Previous tools

+## Previous tools { #previous-tools }

-### <a href="https://www.djangoproject.com/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Django</a>

+### <a href="https://www.djangoproject.com/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Django</a> { #django }

It's the most popular Python framework and is widely trusted. It is used to build systems like Instagram.

It was created to generate the HTML in the backend, not to create APIs used by a modern frontend (like React, Vue.js and Angular) or by other systems (like <abbr title="Internet of Things">IoT</abbr> devices) communicating with it.

-### <a href="https://www.django-rest-framework.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Django REST Framework</a>

+### <a href="https://www.django-rest-framework.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Django REST Framework</a> { #django-rest-framework }

Django REST framework was created to be a flexible toolkit for building Web APIs using Django underneath, to improve its API capabilities.

///

-### <a href="https://flask.palletsprojects.com" class="external-link" target="_blank">Flask</a>

+### <a href="https://flask.palletsprojects.com" class="external-link" target="_blank">Flask</a> { #flask }

Flask is a "microframework", it doesn't include database integrations nor many of the things that come by default in Django.

///

-### <a href="https://requests.readthedocs.io" class="external-link" target="_blank">Requests</a>

+### <a href="https://requests.readthedocs.io" class="external-link" target="_blank">Requests</a> { #requests }

**FastAPI** is not actually an alternative to **Requests**. Their scope is very different.

///

-### <a href="https://swagger.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Swagger</a> / <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification/" class="external-link" target="_blank">OpenAPI</a>

+### <a href="https://swagger.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Swagger</a> / <a href="https://github.com/OAI/OpenAPI-Specification/" class="external-link" target="_blank">OpenAPI</a> { #swagger-openapi }

The main feature I wanted from Django REST Framework was the automatic API documentation.

///

-### Flask REST frameworks

+### Flask REST frameworks { #flask-rest-frameworks }

There are several Flask REST frameworks, but after investing the time and work into investigating them, I found that many are discontinued or abandoned, with several standing issues that made them unfit.

-### <a href="https://marshmallow.readthedocs.io/en/stable/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Marshmallow</a>

+### <a href="https://marshmallow.readthedocs.io/en/stable/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Marshmallow</a> { #marshmallow }

One of the main features needed by API systems is data "<abbr title="also called marshalling, conversion">serialization</abbr>" which is taking data from the code (Python) and converting it into something that can be sent through the network. For example, converting an object containing data from a database into a JSON object. Converting `datetime` objects into strings, etc.

///

-### <a href="https://webargs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Webargs</a>

+### <a href="https://webargs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Webargs</a> { #webargs }

Another big feature required by APIs is <abbr title="reading and converting to Python data">parsing</abbr> data from incoming requests.

///

-### <a href="https://apispec.readthedocs.io/en/stable/" class="external-link" target="_blank">APISpec</a>

+### <a href="https://apispec.readthedocs.io/en/stable/" class="external-link" target="_blank">APISpec</a> { #apispec }

Marshmallow and Webargs provide validation, parsing and serialization as plug-ins.

///

-### <a href="https://flask-apispec.readthedocs.io/en/latest/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Flask-apispec</a>

+### <a href="https://flask-apispec.readthedocs.io/en/latest/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Flask-apispec</a> { #flask-apispec }

It's a Flask plug-in, that ties together Webargs, Marshmallow and APISpec.

///

-### <a href="https://nestjs.com/" class="external-link" target="_blank">NestJS</a> (and <a href="https://angular.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Angular</a>)

+### <a href="https://nestjs.com/" class="external-link" target="_blank">NestJS</a> (and <a href="https://angular.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Angular</a>) { #nestjs-and-angular }

This isn't even Python, NestJS is a JavaScript (TypeScript) NodeJS framework inspired by Angular.

///

-### <a href="https://sanic.readthedocs.io/en/latest/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Sanic</a>

+### <a href="https://sanic.readthedocs.io/en/latest/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Sanic</a> { #sanic }

It was one of the first extremely fast Python frameworks based on `asyncio`. It was made to be very similar to Flask.

///

-### <a href="https://falconframework.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Falcon</a>

+### <a href="https://falconframework.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Falcon</a> { #falcon }

Falcon is another high performance Python framework, it is designed to be minimal, and work as the foundation of other frameworks like Hug.

///

-### <a href="https://moltenframework.com/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Molten</a>

+### <a href="https://moltenframework.com/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Molten</a> { #molten }

I discovered Molten in the first stages of building **FastAPI**. And it has quite similar ideas:

///

-### <a href="https://github.com/hugapi/hug" class="external-link" target="_blank">Hug</a>

+### <a href="https://github.com/hugapi/hug" class="external-link" target="_blank">Hug</a> { #hug }

Hug was one of the first frameworks to implement the declaration of API parameter types using Python type hints. This was a great idea that inspired other tools to do the same.

///

-### <a href="https://github.com/encode/apistar" class="external-link" target="_blank">APIStar</a> (<= 0.5)

+### <a href="https://github.com/encode/apistar" class="external-link" target="_blank">APIStar</a> (<= 0.5) { #apistar-0-5 }

Right before deciding to build **FastAPI** I found **APIStar** server. It had almost everything I was looking for and had a great design.

///

-## Used by **FastAPI**

+## Used by **FastAPI** { #used-by-fastapi }

-### <a href="https://docs.pydantic.dev/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Pydantic</a>

+### <a href="https://docs.pydantic.dev/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Pydantic</a> { #pydantic }

Pydantic is a library to define data validation, serialization and documentation (using JSON Schema) based on Python type hints.

///

-### <a href="https://www.starlette.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Starlette</a>

+### <a href="https://www.starlette.io/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Starlette</a> { #starlette }

Starlette is a lightweight <abbr title="The new standard for building asynchronous Python web applications">ASGI</abbr> framework/toolkit, which is ideal for building high-performance asyncio services.

///

-### <a href="https://www.uvicorn.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Uvicorn</a>

+### <a href="https://www.uvicorn.org/" class="external-link" target="_blank">Uvicorn</a> { #uvicorn }

Uvicorn is a lightning-fast ASGI server, built on uvloop and httptools.

///

-## Benchmarks and speed

+## Benchmarks and speed { #benchmarks-and-speed }

To understand, compare, and see the difference between Uvicorn, Starlette and FastAPI, check the section about [Benchmarks](benchmarks.md){.internal-link target=_blank}.

-# Concurrency and async / await

+# Concurrency and async / await { #concurrency-and-async-await }

Details about the `async def` syntax for *path operation functions* and some background about asynchronous code, concurrency, and parallelism.

-## In a hurry?

+## In a hurry? { #in-a-hurry }

<abbr title="too long; didn't read"><strong>TL;DR:</strong></abbr>

But by following the steps above, it will be able to do some performance optimizations.

-## Technical Details